About the National

Scouting Museum

Open to the Public — Free Admission

Late May — Mid-August

Monday — Saturday | 8:00 am — 5:30 pm

Sunday | 8:00 am — 5:00 pm

Mid-August — Late May

Monday — Saturday | 8:00 am — 5:00 pm

Closed Some Holidays

If you’d like more information, please give us a call: (575) 376-1136.

About the National Scouting Museum

The National Scouting Museum shares the rich history of Scouting America with visitors, including the tens of thousands of campers, volunteers, and alumni who visit Philmont each year. The Museum is home to the Seton Memorial Library with reading and research rooms, a gift shop with jewelry, books, and mementos, five exhibit galleries, and an 88-person conference room.

The National Scouting Museum has played an important role in preserving and telling the rich story of Scouting America and the positive impact Scouting continues to have on youth and families for decades. The museum is committed to preserving the rich, 110-plus-year history of the Scouting movement by collecting, organizing, preserving, and displaying some of Scouting’s greatest treasures, including more than 600,000 artifacts.

This collection not only documents Scouting’s unique influence on American culture but also tells the story of a movement that has positively affected the lives of more than 110 million young people. The museum’s move to Philmont (where more than 20,000 people visit annually) exposes even more people to Scouting’s story and introduces unique opportunities to showcase parts of the collection throughout the country. The National Scouting Museum’s Philmont home is the primary place to see Scouting memorabilia, but Scouting America’s expansive collection of Scouting collectibles will be spread far and wide. Additionally, we are working hard to make many parts of the collection and archives digitally accessible. It allows Scouting America to establish displays and exhibits at the three other national high adventure bases: the Summit Bechtel Reserve in West Virginia, the Florida Sea Base, and the Northern Tier National High Adventure Bases in Minnesota and Canada, as well as the possibility for some items to be loaned to local councils for display in their facilities. All of this means that more scouts get a glimpse into Scouting America’s powerful past.

Camping gear, uniforms, service projects, and more tell the story of Scouting in the Scouting Heritage Gallery, sponsored by the Smart Family Foundation. The history of Philmont Scout Ranch, Northeast New Mexico, the Santa Fe Trail, and Ernest Thompson Seton are featured in separate galleries in the second half of the Museum. Study the ranch’s trails and camps on an oversized, 3-D topographical map, learn more about an 1850s mud wagon, view southwestern pottery, and learn about the artwork of Ernest Thompson Seton.

Museum Collections

Notable Collections Pieces from the History of Scouting

National Scouting Museum Collections

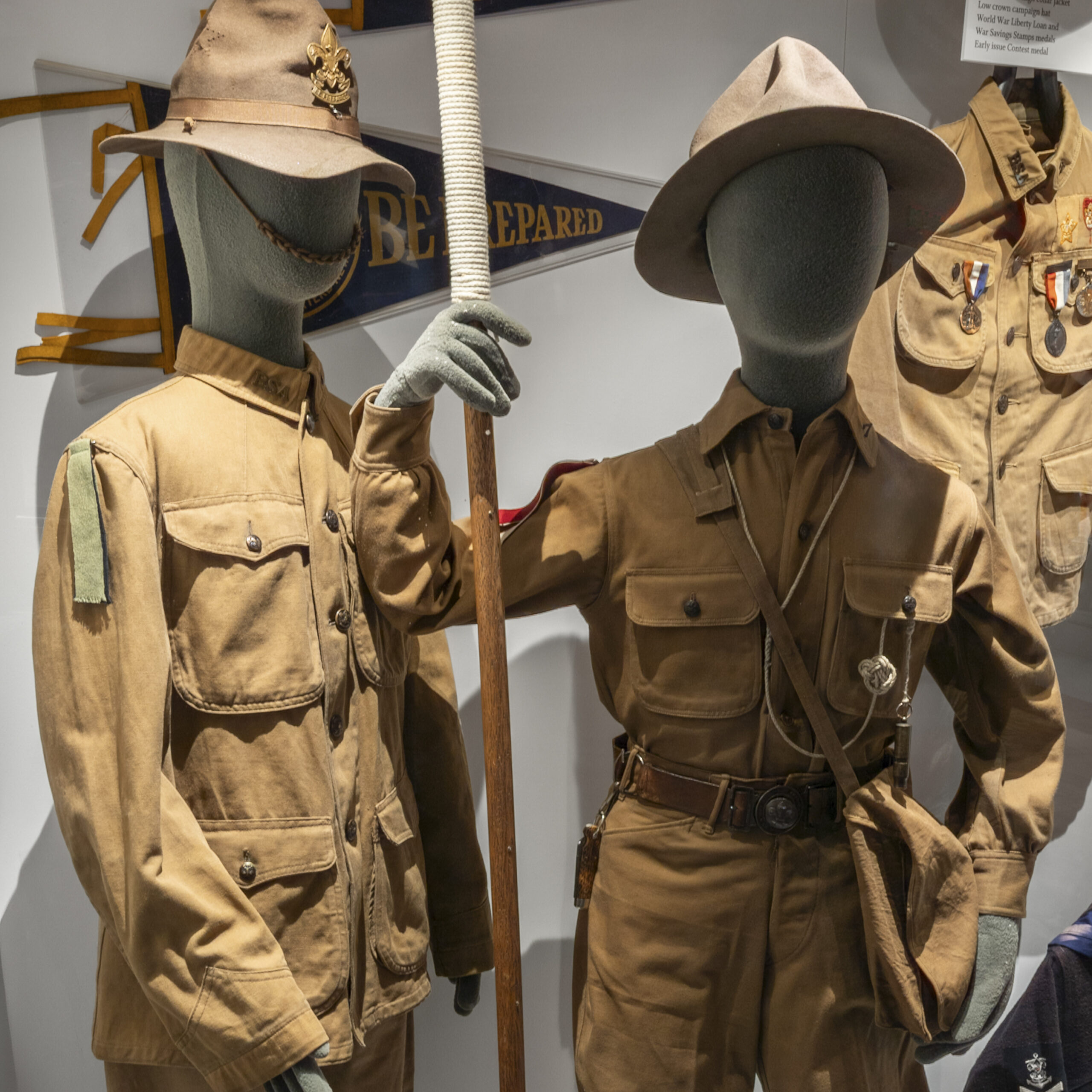

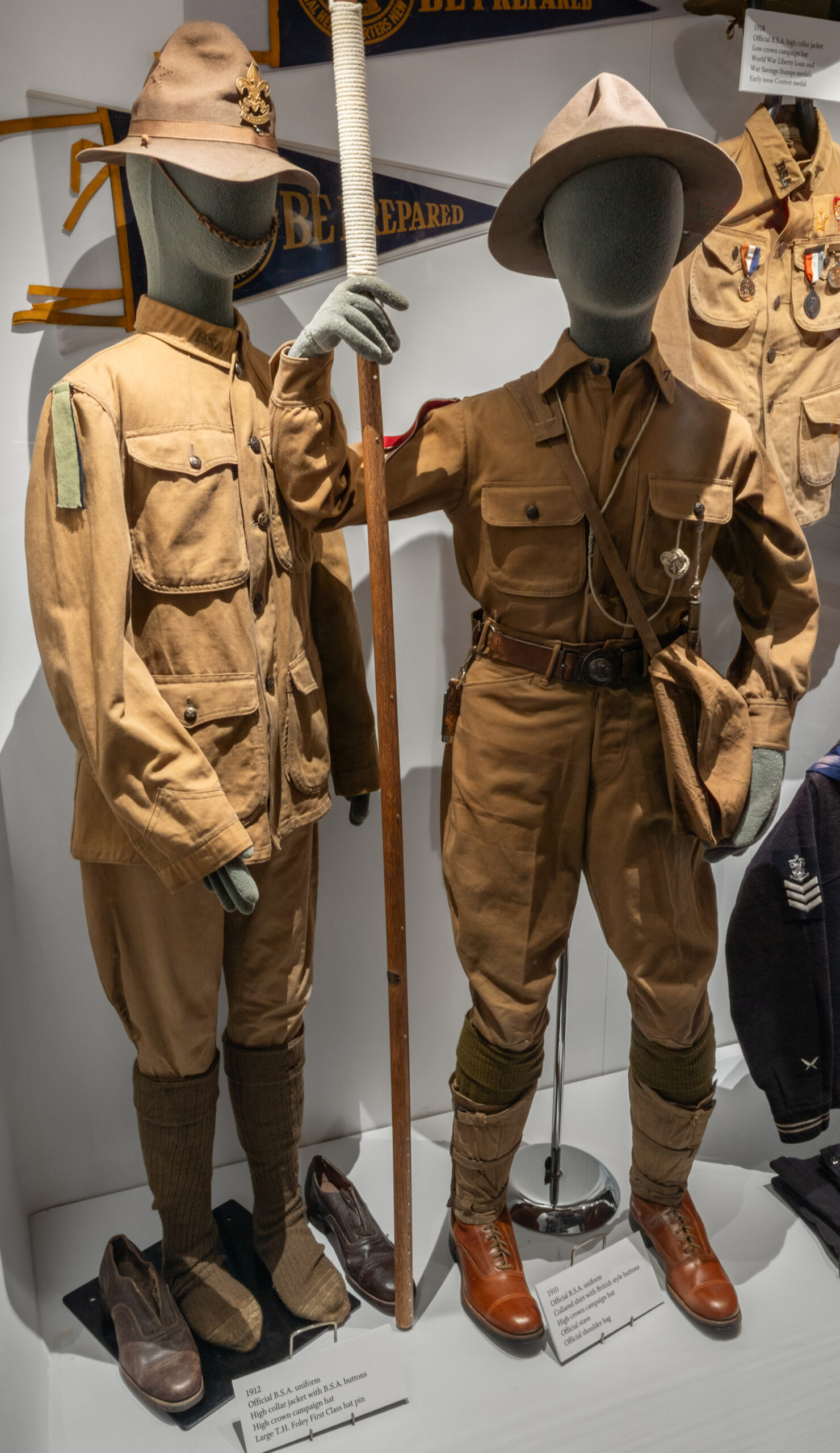

The uniform identifies a Scout as a member of the World Brotherhood of youth who share the same ideals.

The BSA has operated a variety of unique programs through the years. Some of them have had their own uniform or special insignia for the traditional uniform.

The style of the scout uniform has also evolved over time, as seen from these examples.

Left Uniform

- 1912 Official B.S.A. Uniform

- High Collar Jacket with B.S.A. Buttons

- High Crown Campaign Hat

- Large T.H. Foley “First Class” Hat Pin

Right Uniform

- 1910 Official B.S.A Uniform

- Collared Shirt with British-Style Buttons

- High Crown Campaign Hat

- Official Stave

- Official Shoulder Bag

National Scouting Museum Collections

- Personal Health

- Plumbing

- Gardening

- Cooking

- Painting

- Swimming

- Civics

- Lifesaving

- Public Health

- Cycling

- Pathfinding

- Interpreting

- Electricity

- Dairying

- First Aid to Animals

- Chemistry

- Business

- Handicraft

- Firemanship

- Horsemanship

- Poultry Farming

National Scouting Museum Collections

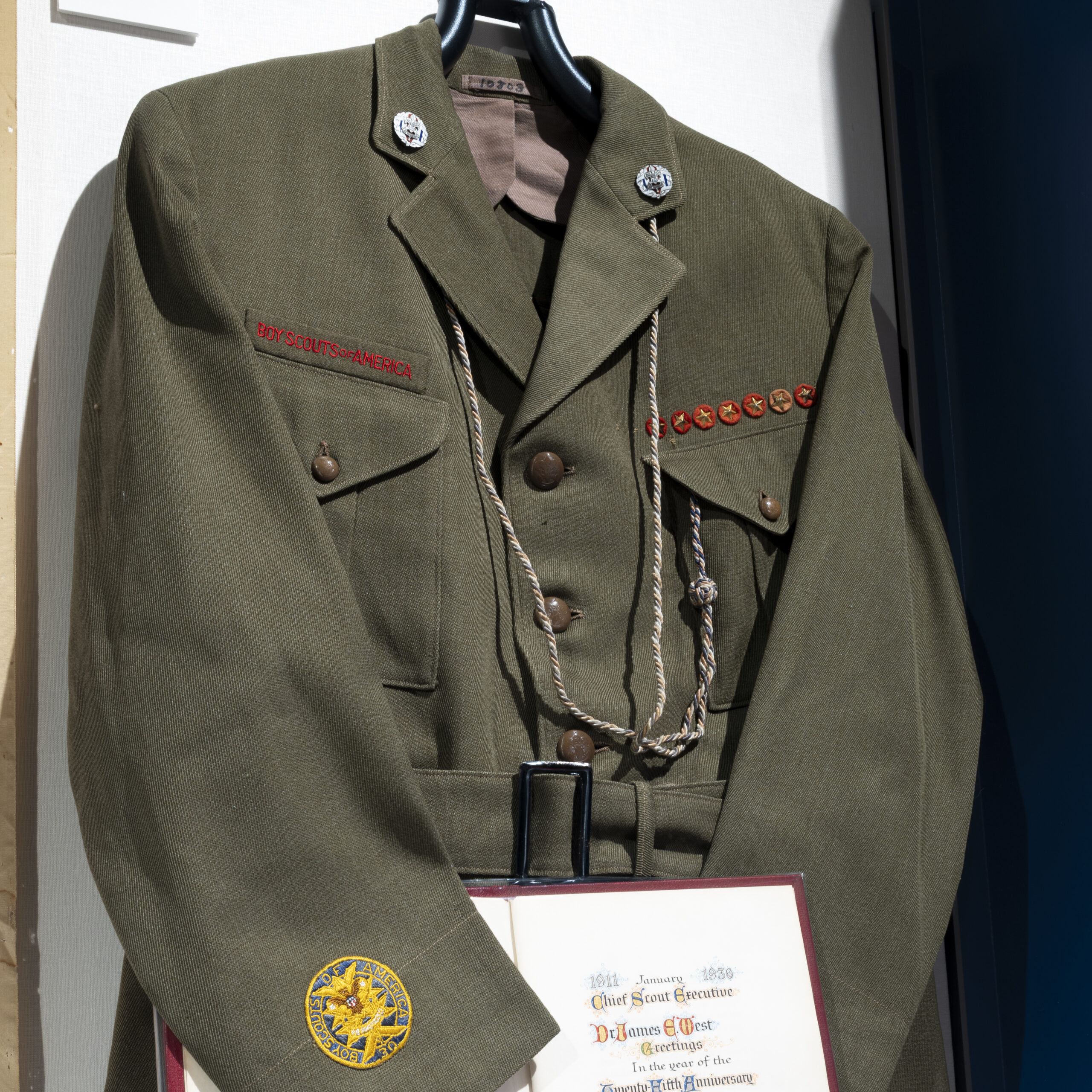

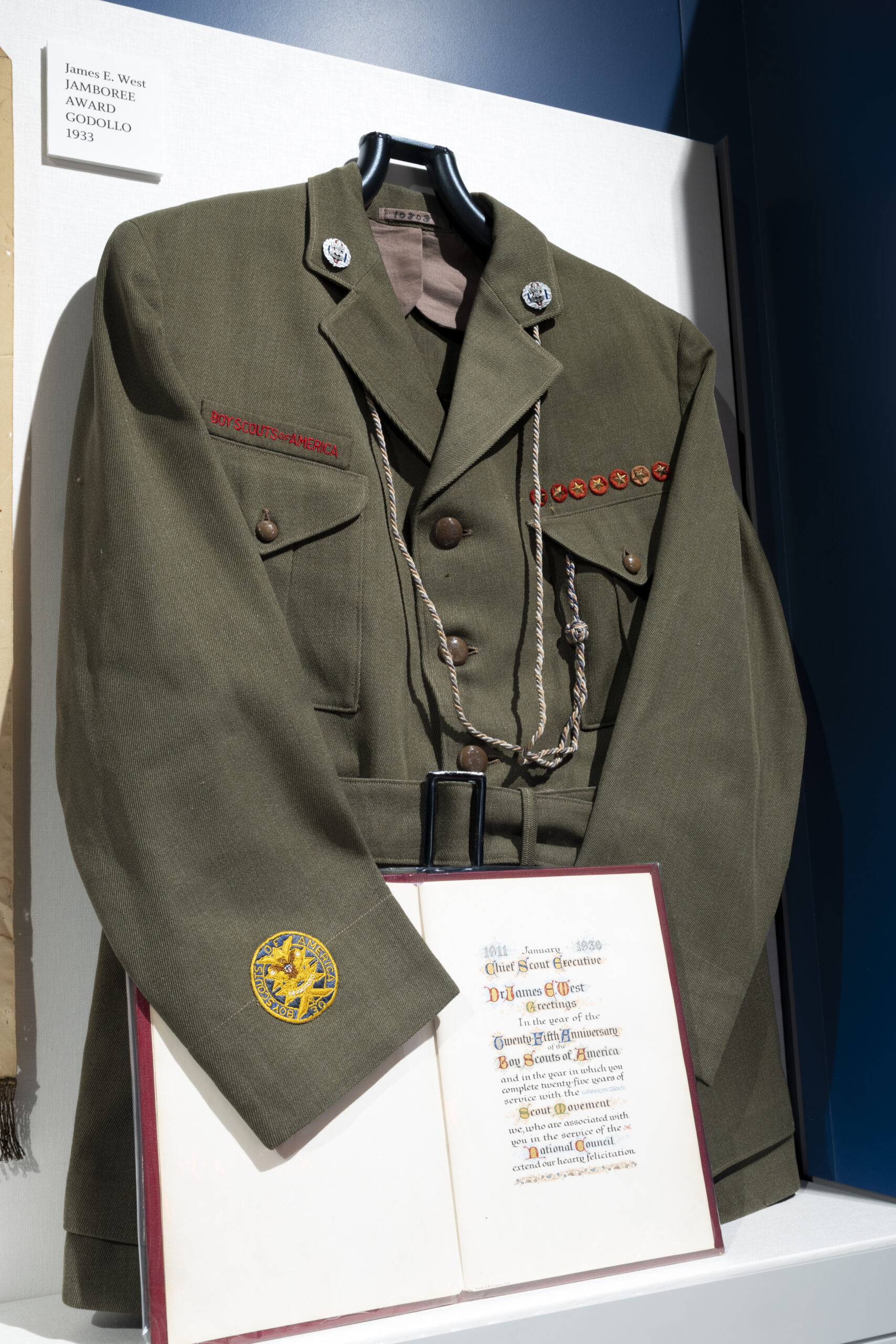

James E. West spent his youth in a Washington, D.C. orphanage. Suttering from tuberculosis in one of his legs, he was drawn to academics. He convinced the orphanage matron to let him create a library at the institution, and paid the younger children a penny for each book they read. He worked as a newspaper editor and math tutor during high school and, despite his disability, taught himself to ride a bicycle so he could work at a cycling shop.

While attending law school, West began his professional career with the YMCA. In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him to a position in the Department of the Interior. Continuing his high level service to American Youth in Washington, West directed the National Child Rescue League and the White House Conference on Dependent Children, both of which supported orphanages and orphans.

With this outstanding record as an advocate for our nation’s youth, West was offered the opportunity to be BSAs first Executive Secretary. His decision to lead the novel BSA was risky but atter much persuasion West accepted the position in 1911 on a temporary basis and moved to New York City. He spent the next 32 years as our first Chief Scout Executive.

The impact of James E. West’s tenure as first and longest-serving Chief Scout Executive is unmatched. Under his leadership, West nurtured BSA from a one-room office into a flourishing national organization with over 500 local councils throughout the country at the time of his retirement in 1943. West contributed to American history by establishing BSA as a national institution which is now woven into the very fabric of our country’s culture.

James E. West died in 1948 at the age of 71.

National Scouting Museum Collections

The format used for this jamboree was a competition among the contingents from each country – a Scout Olympics.

The BSA contingent won several of the individual competitions as well as the overall championship. They received the three cups displayed here for their accomplishments. After the jamboree, Baden-Powell decided that this was not the right choice for a world jamboree, fearing that such competition was not in keeping with his vision for Scouting to be a world brotherhood.

National Scouting Museum Collections

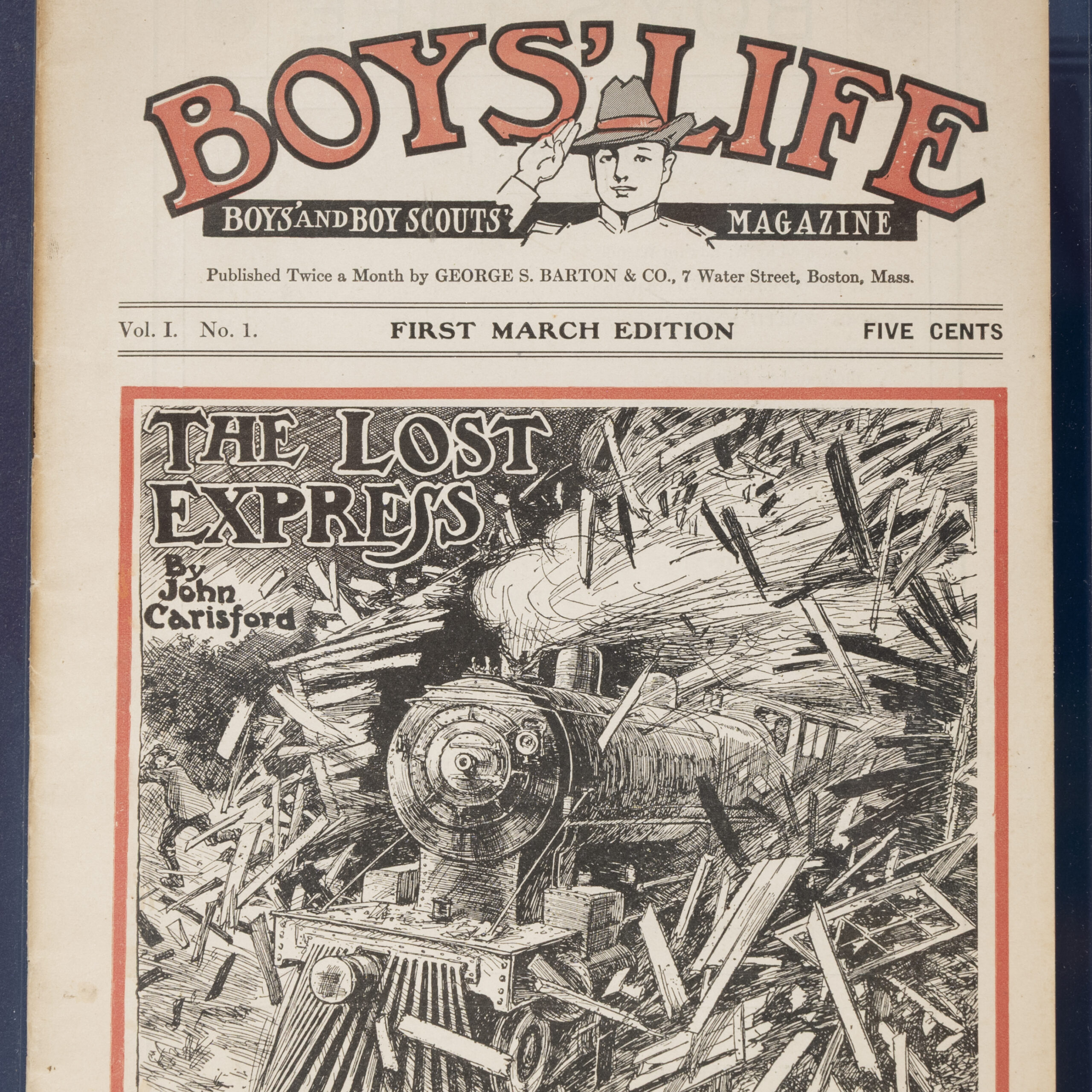

In January 1911 George Barton published the first edition of Boys’ Life magazine. An expanded and modified Vol. 1 No. 1 was published in March 2011.

In 1912, Dr. James West purchased the rights to the magazine and the first official BSA issue appeared in July. The magazine was later retitled to “Scout Life” in January 2021. Publication of Scouting for adult leaders began in 1913.

The last paper issue was May-June 2020. It is now available as a digital app.

National Scouting Museum Collections

The Eagle Scout Rank Patch and the Merit Badge Sash were created in 1924 for the 60 Boy Scouts representing the BSA at the 1924 World Jamboree in Denmark.

The Eagle Scout Rank Patch and the Merit Badge Sash were created in 1924 for the 60 Boy Scouts representing the BSA at the 1924 World Jamboree in Denmark.

During the Summer of 2021, Andrew Morgan, a NASA Astronaut, came to Philmont on a trek with his Troop from Houston, Texas. The other adult advisor to the crew was fellow Astronaut Kjell Lindgren.

In 2022, Eagle Scout Kjell Lindgren carried this 1924 Eagle Scout Patch aboard SpaceX Crew Dragon 2 – Freedom to the International Space Station for ISS Expedition 67/68. Lindgren served as the Spacecraft Commander aboard Freedom which launched on April 22, 2022.

During their time in space, Lindgren and his fellow astronauts, along with the Eagle Scout patch, traveled approximately 71,916,800 miles during their 2,720 orbits. After spending 170 days in space, Lindgren and the Eagle Scout patch returned to Earth on October 14, 2022.

This is a copy of the loan agreement between the National Scouting Museum and NASA. Lindgren returned the Eagle Scout patch to the NSM in September 2023 as part of the BSA’s National Outdoor Conference hosted at Philmont Scout Ranch.

Honor Medals for Lifesaving

National Scouting Museum Collections

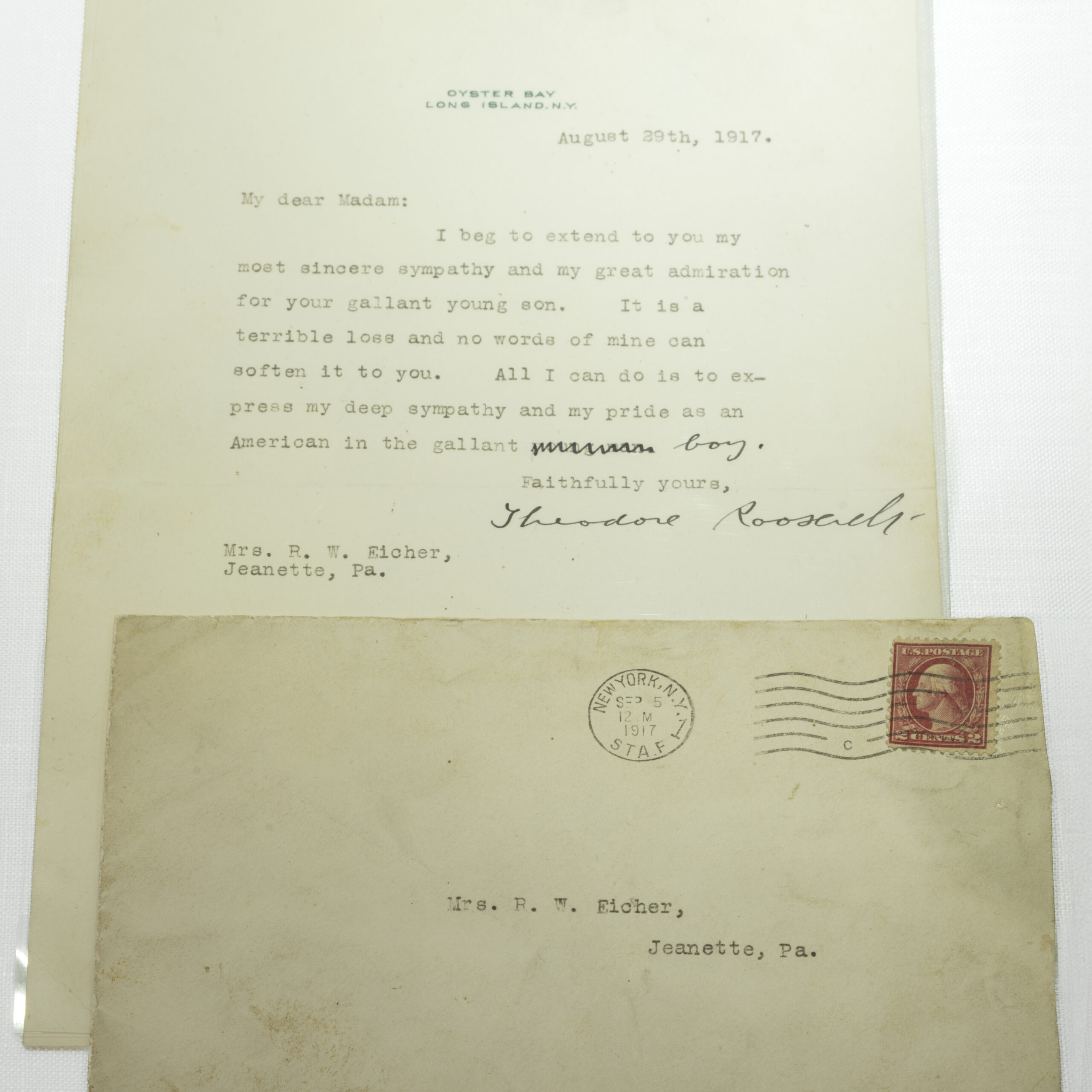

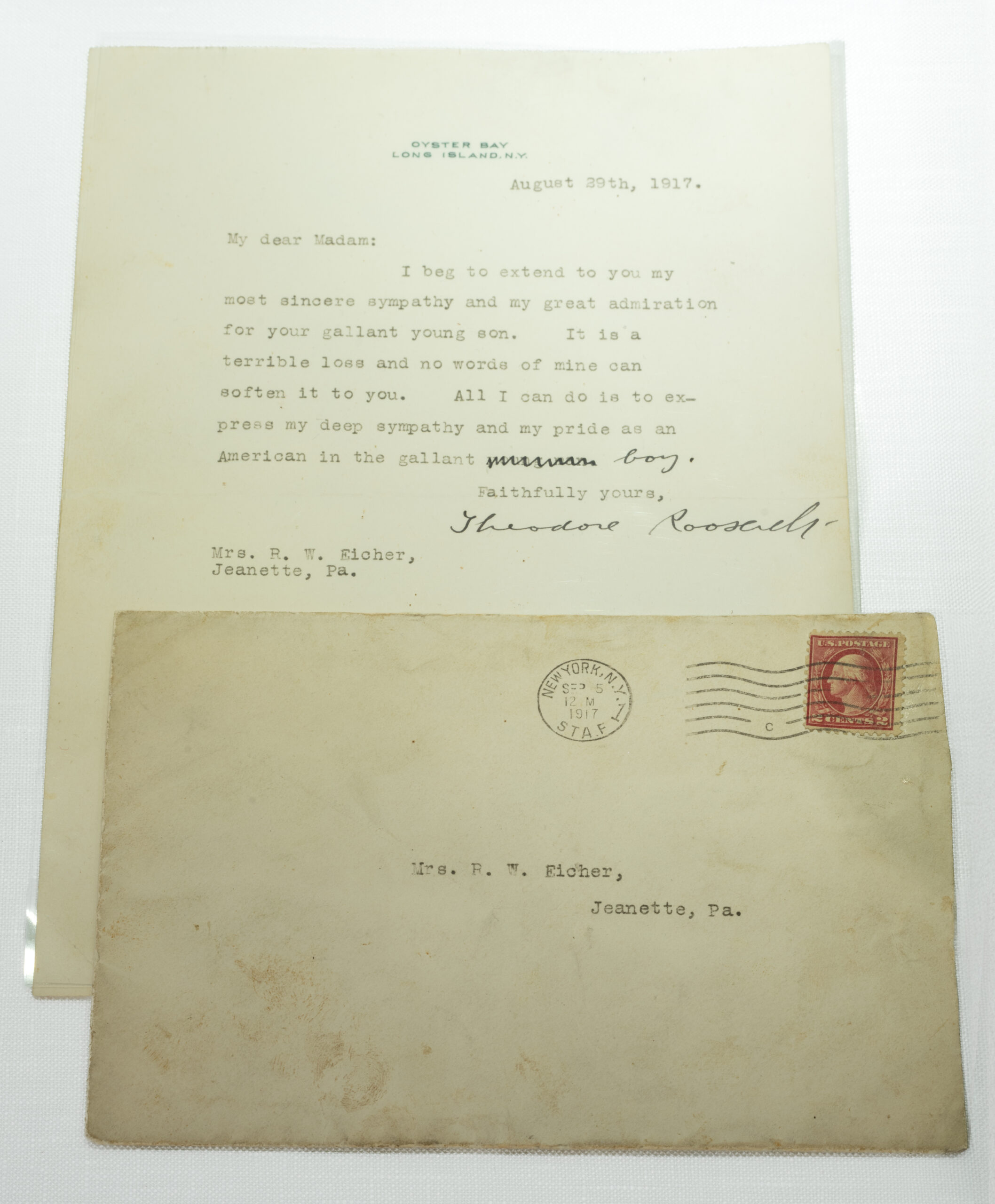

The first Gold Honor Medal recipient was Second Class Scout Robert Eicher of Jeanette, PA. He died on August 11, 1917 attempting to save a young girl, Mazie Mugg from drowning. Here is an excerpt of his rescue attempt from official records….

“A poor swimmer, he had no life-saving experience. A young girl who had just learned to swim went down to the creek to show them how well she could do it. She jumped into the water – a stream, with a strong current and whirlpools and was in trouble.

Robert came running to the stream and jumped in with his clothes and scout shoes on. Drawn down again and again as they were swept down-stream, he tried his best, but towing another person in a strong current was too much for him. He went down in the end still fighting and refusing to relinquish his hold on the girl he attempted to rescue. The girl’s body was recovered shortly after, but Robert’s was caught under a stone, and was not brought up for three hours.”

On August 29, 1917, only a few days after young Robert’s heroic action and sacrifice, Chief Scout Citizen Theodore Roosevelt sent a letter of condolence and appreciation to his parents. Ultimately, this may have had some bearing on the ultimate action of the National Court of Honor to include Robert in the first four Gold Honor Medal awards.

National Scouting Museum Collections

Russell Grimes, a First Class Scout from Broken Bow NE was working at a ranch helping to haul heavy logs on a wagon drawn by a four-horse team. Grimes was operating the brake at the rear of the wagon when something startled the horses and they broke into a run down the rough roadway. Russell could have jumped clear, but he put all his might into the brake as the driver pulled on the reins. The horses swerved, the wagon jumped off the roadway and turned over. Both brake-boy and driver were thrown clear. Scout Grimes came down on his head and never regained consciousness. The driver was severely injured, but his life saved due to Grimes’ tenacity.

An elderly member of his community recalls that upon receiving the Gold Medal from the BSA, Grimes’ father had his grave exhumed and pinned the medal on the uniform in which his young heroic body was buried.

National Scouting Museum Collections

Edward Goodnow was a sixteen-year-old scout from Springfield MA. On August 29, 1917, he drowned in Shaker Pond in Enfield CT while attempting to save the second of two drowning boys. The below photo shows young Edward with one of those same boys.

Edward had a twin sister named Ruth. She married George Martel and named her two sons George Edward Martel and Edward Martel in honor of her heroic brother.

The medal and photo were donated to the National Scouting Museum by the Martel family.

National Scouting Museum Collections

Twelve-year-old Tenderfoot Scout George Gordon Seyfried of South Orange NJ had only been a Scout for a few months when one day he saw his mother’s maid with a revolver, intent on suicide, about to shoot herself. The maid was a robust young woman, much heavier than young George. She was despondent and desperate over a love affair that ended badly. The account of his heroic action reads….

“Scout Seyfried knew nothing about handling a situation such as this. He grasped the girl’s wrist, and tried to wrench the gun from her hand. In the struggle the gun went off, and the bullet passing through the girl’s left breast struck him in the neck. The girl recovered from her injury (the bullet glanced off her ribcage), but the boy’s wound proved fatal. In the hospital, just before he died, Gordon Seyfried whispered to his mother: ‘I tried to do my duty as a Boy Scout.’ “

One newspaper account of Gordon Seyfried’s sacrifice surmised that his valiant attempt was just fulfilling his promise as a Scout to “do his good turn daily.” The newspaper noted that the Boy Scout good turn included everything from “filling mother’s wood box to feeding a hungry dog.” And added… “There is no limit to its scope.”

This medal was acquired from John C. Seyfried of Sedonna AZ, the grandson of John E. Seyfried, the younger brother of George.

Notable Collections Pieces of the Seton Memorial Library

The Seton Memorial Library houses Ernest Thompson Seton’s personal library due to the generous donation of Julia Seton in 1967. The library is available for visitors, participants, and staff to view books about the southwest, Philmont, and the areas surrounding Philmont.

National Scouting Museum Collections

In January 1891, Ernest Thompson Seton traveled to Paris to study and paint at the L’Academie Julian, an art school made up of expatriate Canadian artists. While the other artists in the school concentrated on painting classical representations of landscapes and human forms, Seton chose to paint his favorite subjects: wild animals, particularly wolves. His first effort was a wolf painted like one at the Paris zoo that he titled Sleeping Wolf. The painting was accepted in the prestigious juried show at the Grand Salon.

The next year, Seton began work on a large genre, or storytelling, world painting. He had read an unsubstantiated report in a Paris newspaper about a Pyrenees woodsman who was known for hunting sheep-killing wolves. One evening, the Pyrenees woodsman failed to return to his cottage. The next morning he was found dead, apparently killed by wolves.

The unproven story intrigued Seton and, given his compassion for wolves, he set about to put it on canvas. He titled the resultant panting, Triumph of the Wolves, giving it the implied moral that man cannot conquer nature and that man should respect nature rather than attempt to dominate it. Later, he gave it a second title, Awaited in Vain, which allowed it to be contemplated by the viewer either in sympathy for the wolves or the hunter.

Despite Seton’s demonstrated technical ability in carrying out the painting, it was rejected by the jury for the 1892 Grand Salon show due to its gruesome subject matter. However, the painting was hung in 1893 as part of the Canadian exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair.

National Scouting Museum Collections

Lobo (Spanish for “wolf”) was the leader of a wolfpack that roamed the Currumpaw River Valley of northeastern New Mexico in the early 1890s. He and his pack were notorious for preying on the vast cattle and sheep herds of the area.

For several years local ranchers tried to trap and kill the members of the pack. Lobo possessed such cunning, however, that he was able to detect their poisons and traps.

Due to his knowledge of wolf behavior, Ernest Thompson Seton, a naturalist and the author of the Boy Scout Handbook, was employed by the ranchers to rid them of Lobo’s pack. His first attempts at trapping and poisoning were to no avail. However, he learned that a small, white wolf called Blanca often ran ahead of the pack. Seton concluded that the wolf must be a female, for Lobo would have killed any male committing a similar act. Later he determined that the white wolf was, in fact, Lobo’s mate.

Having identified the big wolf’s mate, Seton set about to capture her. He killed a cow as bait, severed the head from the body and set traps around both. When Lobo and the pack came to inspect the kill, Blanca broke in front and was caught in one of the traps.

Seton killed Blanca and used her body and scent to lure Lobo into traps. He tried to keep Lobo alive, but the great wolf eventually died suffering from the loss of both his freedom and his mate.

Seton recounted the capture of Lobo in his most famous book, Wild Animals I have Known (1898).

National Scouting Museum Collections

Ernest Thompson Seton began this painting in 1894. It depicts the view from a Russian trapper’s sled that is being pursued by wolves. Seton derived the scene from a story he later published in Forest & Stream titled, “The Baron and the Wolves.”

Ernest Thompson Seton began this painting in 1894. It depicts the view from a Russian trapper’s sled that is being pursued by wolves. Seton derived the scene from a story he later published in Forest & Stream titled, “The Baron and the Wolves.”

Although the painting’s meaning is ambiguous, one scholar has postulated that Seton “meant to show wicked men pursued by vengeful wolves retaliating against man’s destruction of nature”. Seton took great care in preparing elaborate studies of each of the twelve wolves in the pack. In addition, he did several other studies to work out the color scheme and arrangement of the finished painting.

The painting was completed in January of 1895 and was submitted for hanging in the Grand Salon of Paris. The painting was rejected, perhaps because the message was not easily understood. Nevertheless several of the studies were accepted and displayed.

President Theodore Roosevelt was so impressed with the painting that he commissioned Seton to paint a canvas of the lead wolf. The resulting painting hung in the Roosevelt Gallery for many years. It was also used as the frontispiece of Volume II of Seton’s Life Histories of Northern Animals.

Notable Collections Pieces from the History of Cimarron, NM

National Scouting Museum Collections

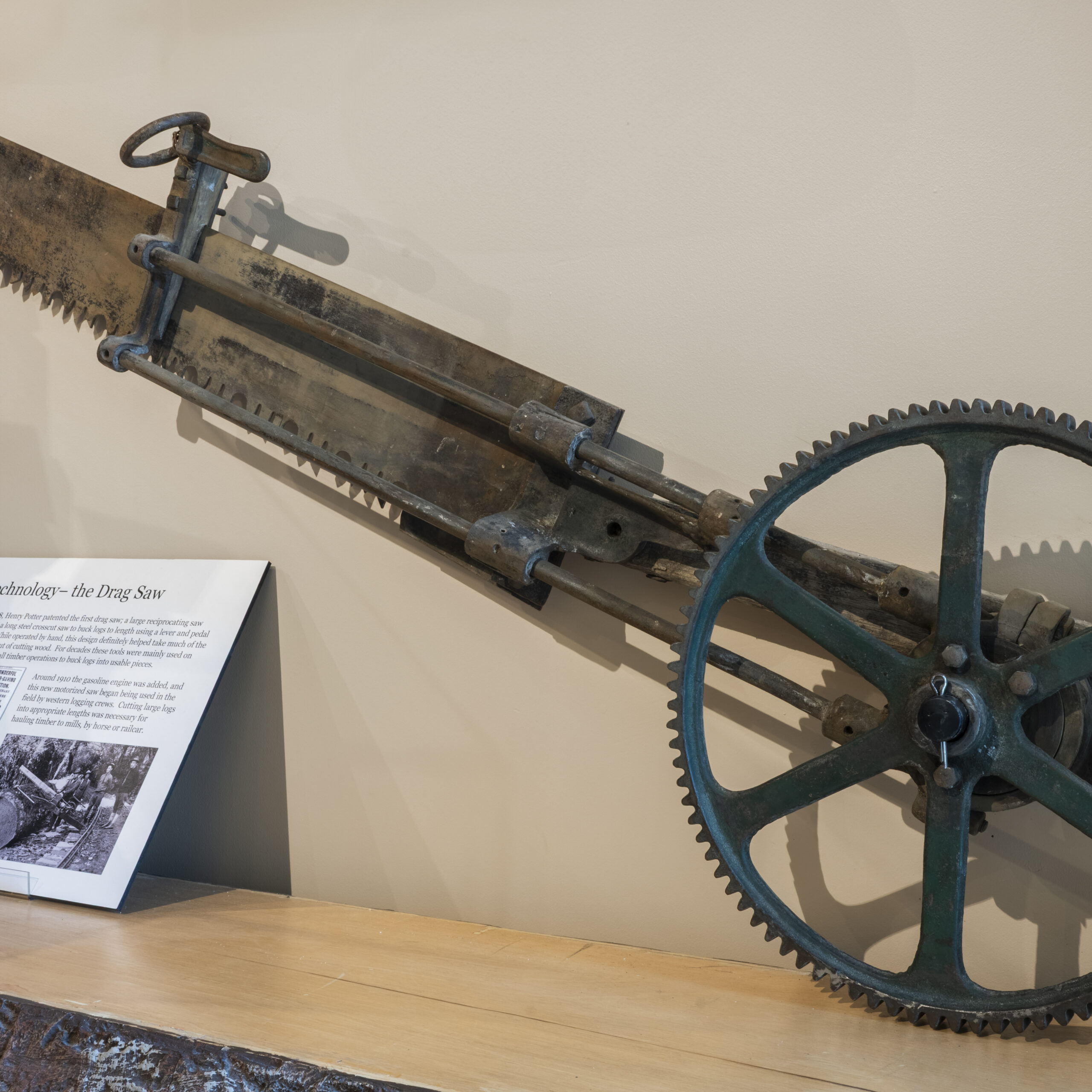

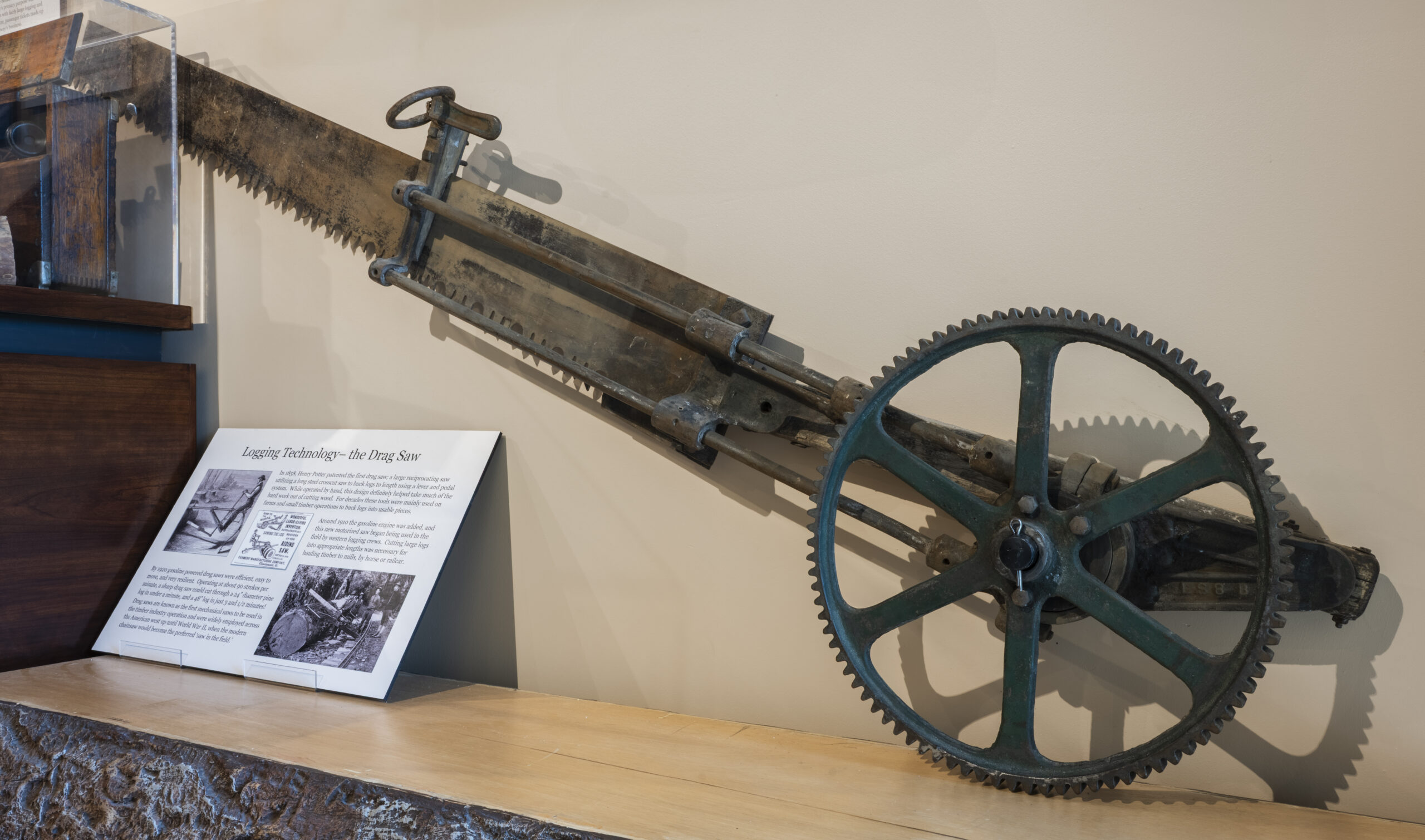

In 1858, Henry Potter patented the first drag saw; a large reciprocating saw utilizing a long steel crosscut saw to buck logs to length using a lever and pedal system. While operated by hand, this design definitely helped take much of the hard work out of cutting wood. For decades these tools were mainly used on farms and small timber operations to buck logs into usable pieces.

Around 1910 the gasoline engine was added, and this new motorized saw began being used in the field by western logging crews. Cutting large logs into appropriate lengths was necessary for hauling timber to mills, by horse or railcar.

By 1920 gasoline powered drag saws were efficient, easy to move, and very resilient. Operating at about 90 strokes per minute, a sharp drag saw could cut through a 24″ diameter pine log in under a minute, and a 48″ log in just 3 and 1/2 minutes!

Drag saws are known as the first mechanical saws to be used in the timber industry operation and were widely employed across the American west up until World War II, when the modern chainsaw would become the preferred ‘saw in the field.

Continental Tie & Lumber Company

Established in 1907 by Theodore A. Schomburg

As the coal mining industry exploded in the Dawson and Raton regions of New Mexico so did the demand for mine timbers, rail ties, and quality lumber. Schomburg estimated that the Ponil canyons, rich with old growth timber, could be profitably logged for the next twenty years. Early estimates claimed there was enough timber for 2 million rail ties alone. As the railway moved in so did the logging crews. Some loggers were independent, while others worked for the company, but most every crew specialized in either rail ties, mine props, or lumber grade timber. Within each crew, men were divided into undercutters, sawyers, axemen, and haulers. Once the timber was down, limbed, and cut to length it was loaded on a wagon or skidded with draft horses to the closest sawmill or railway stop.

In the beginning, rail ties were hewn by hand, but by 1915 most were being sawn at small mills, loaded on the train, and shipped to the Continental Tie & Lumber Company’s new treatment plant in Cimarron. The plant used pressurized zinc chloride and it quickly brought in huge profits for the C.T. & L. Co. It was so successful that in 1920, Guy Palmes and Schomburg’s son Thomas built a large, modernized sawmill next door. This new mill, owned by C.T. & L. Co., was capable of processing 30,000 board feet of lumber a day. Soon the small mountain mills closed down as logs were being shipped directly to Cimarron on the Cimarron & Northwestern Railway, further increasing the company’s profits.

By 1923, quality timber ran out in the North Ponil country and logging moved to Wilson Mesa and the South Ponil Canyon. Initial prospects were encouraging but as cutting began they found that many stands of the old growth timber around the mesa suffered from dry rot. By 1932 the C.T. & L. Co. would sell off their equipment.

Logging the Ponil country was over. Schaumburg was correct; there was only about 20 years of profit in those Ponil forests!

National Scouting Museum Collections

Prior to the 20th Century, the only light available for mining were from candles or oil wick lamps. Candles were mainly held in a metal coil with a sharp point that could be pushed into a crack in rock or timber. Oil wick lamps were either hung from the miners hat or placed wherever there was a flat spot.

In 1910, the invention of carbide lamps quickly replaced the candles and oil lamps. Carbide lamps are powered by the reaction of calcium carbide with water. This reaction produces acetylene gas which burns a clean, white flame. These lamps could be used as stationary lighting as well as being attached to a Miner’s hat or helmet.

Personal electric head lamps, powered by batteries, came into use in 1938.

Baldy Mining District

In 1866, a hunting party of Ute Indians had been in search of wild game on the high slopes of Baldy Mountain. Whether they found any is unknown, but we do know that the pretty green rocks that they picked up made a huge impression on William H.

Moore and several soldiers from Fort Union. Excited, the soldiers made their way to Baldy Mountain, and found a thick carpet of “copper float” in the high talus fields.

They staked their claim, and called it Mystic Lode. By October, Moore had gathered investors and sent Pete Kinsinger, Larry Bronson, and a man named Kelly back to the mountain. Their plan was to follow Willow Creek up the mountain to collect and prepare to ship as much copper ore as possible before the winter snows arrived. As luck would have it, they never made it to the Mystic Lode. One evening while camping next to that creek Kelly did a little prospecting of his own…

“GOLD! I FOUND GOLD!!”

Finding gold is a pretty hard secret to keep.

Soon hundreds were headed to Baldy Mountain in search of gold, riches, and staking their own claim. By 1867, the western slopes became the Willow Mining District and the Moreno Valley boomed!

A new technique called hydraulic mining seemed to be quite efficient on these slopes, as long as there was plenty of water!

Quick to capitalize on this new discovery, Lucien Maxwell, owner of the land grant on which most of the mountain was located, began collecting rent. He then created the Baldy Mining District and staked a claim in the most promising location for himself farther up the mountain, which he called the Aztec Lode. Up at these higher elevations hard Rock mining was essential as well as profitable. As fate would have it Maxwell’s Aztec Mine would prove to be one of the richest lodes of the century in the Western United States.

As news of the strike spread, camps blossomed into towns. Several companies built housing, stores, and even stamp mills to process the ore. But the initial boom would be short lived and by 1875 only those with especially rich claims would remain. Over the next 65 years mining would come and go, dying out and being revived as the economy, legislation, and industry dictated.

Baldy Town & Maxwell’s Aztec Mine

A second boom came in 1880 and Baldy Town, which had been abandoned in 1872, began to flourish. By 1881 it was home to 800 miners, a stamp mill, saloon, store, post office, hotel and 2 large boarding houses. Hotel Baldy boasted a “high class” bar with two dining rooms! Baldy Town’s population spiked at 2,000 in 1883, and then quickly withered. By 1897 the town was thriving again as the mining district boasted 4 stamp mills and 12 productive mines. With over 200 residents there were plenty of amenities; a hotel, general store, blacksmith, livery stable, saloon, laundry, tailor, barber, public school, Justice of the Peace, Methodist Church, and even a telephone line. Again, prosperity was short lived and mining operations ceased in 1899 when The Aztec Gold Mine and Milling Company lost its’ financial backing.

Work in the Baldy Mining District was steady from 1908 through 1940, but increasingly difficult and Baldy Town would never truly boom again. Hard rock mining was difficult enough, but with 1918 Spanish Influenza epidemic, a large fire in 1923, a fixed gold market from 1902-1930, the Great Depression in 1929, and finally

WWII, gold mining on Baldy finally became too much of a struggle. In 1941 the mines were officially closed, and Baldy Town was abandoned. While over one hundred claims were laid on Baldy Mountain, Maxwell’s Aztec Mine would prove to be champion, yielding over $4 Million in gold. That’s about $250 Million in today’s market !

National Scouting Museum Collections

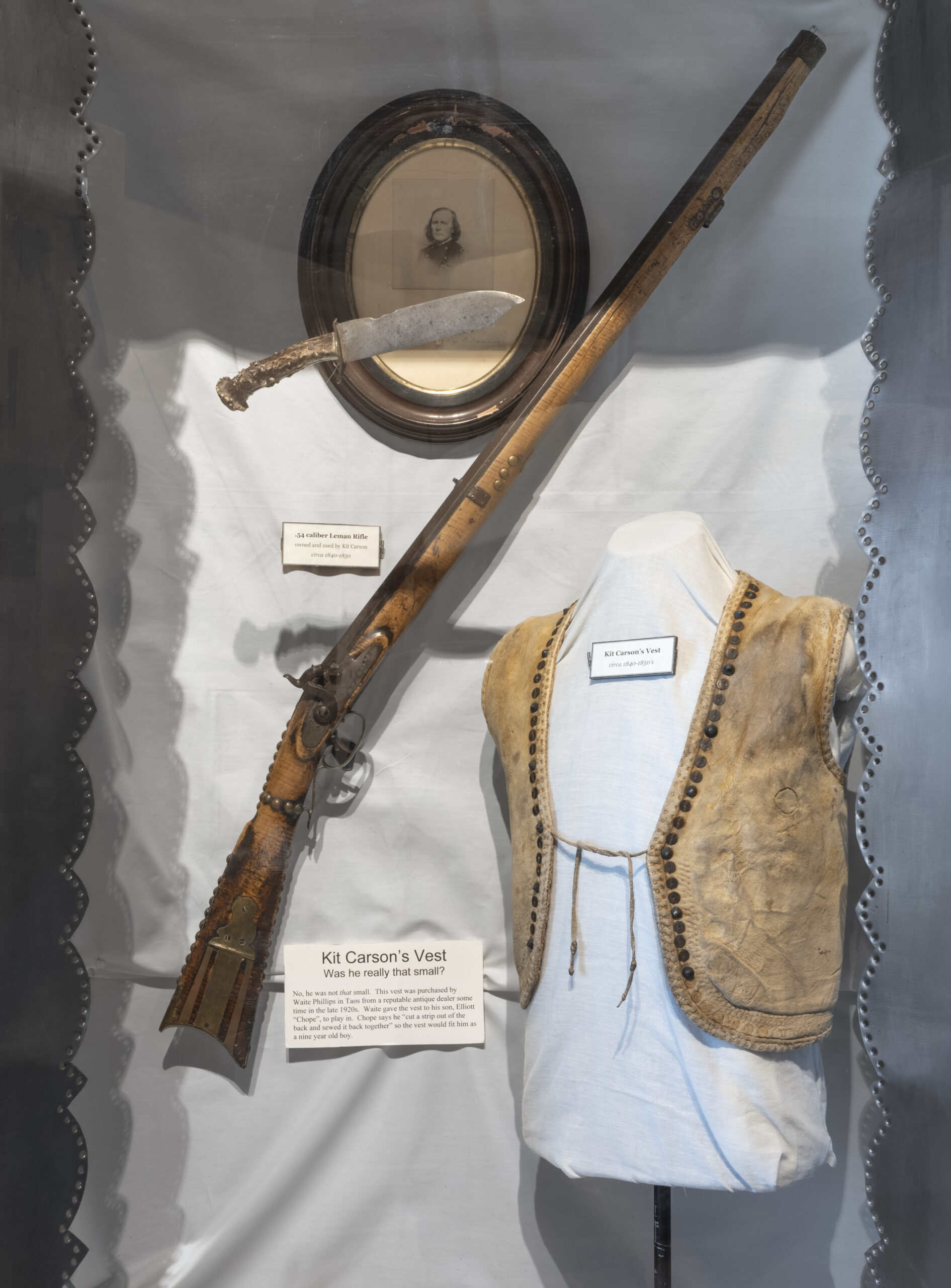

Kit Carson’s Vest

Was he really that small?

No, he was not that small. This vest was purchased by Waite Phillips in Taos from a reputable antique dealer some time in the late 1920s. Waite gave the vest to his son, Elliott

“Chope”, to play in. Chope says he “cut a strip out of the back and sewed it back together” so the vest would fit him as a nine year old boy.

Learn more about Christopher “Kit” Carson by visiting the Kit Carson Museum at Rayado.

Notable Collections Pieces from the History of Philmont

National Scouting Museum Collections

The first camping season was 1939.

Even with an aggressive advertising campaign to attract scouts from around the country, only 180 Scouts came to Philturn Rockymountain Scout Camp in the Ponil area between June 12 and August 31. Each was given a unique patch as “Pioneer Campers.”

This example is one of only a few of these patches known to still exist.

Several years ago, an individual attempted to forge copies of both this patch and the Philturn dollar patch.

National Scouting Museum Collections

They were called “Philmont Guides” in the early 1950s. In the beginning, they worked out of backcountry base camps.

Since the creation of the Ranger Department in 1957, thousands of young men and young women have served in the position and earned the neckerchiefs and badges associated with being a Philmont Ranger.

The first Ranger neckerchief was issued in 1957 and every year since. The first Ranger jacket patch was made in 1969.

The first few years these were dated and there have been a couple designated for anniversaries. One even includes the Ranger battle cry… “I Wanna Go Back to Philmont.”

National Scouting Museum Collections

After the first season in 1939, the Philturn “dollar” patch was introduced to recognize participation in a Philturn Rocky Mountain Scout Camp program. With the second gift of property in 1941, the dollar patch was converted from “Philturn” to “Philmont” to honor the rebranding of the camp.

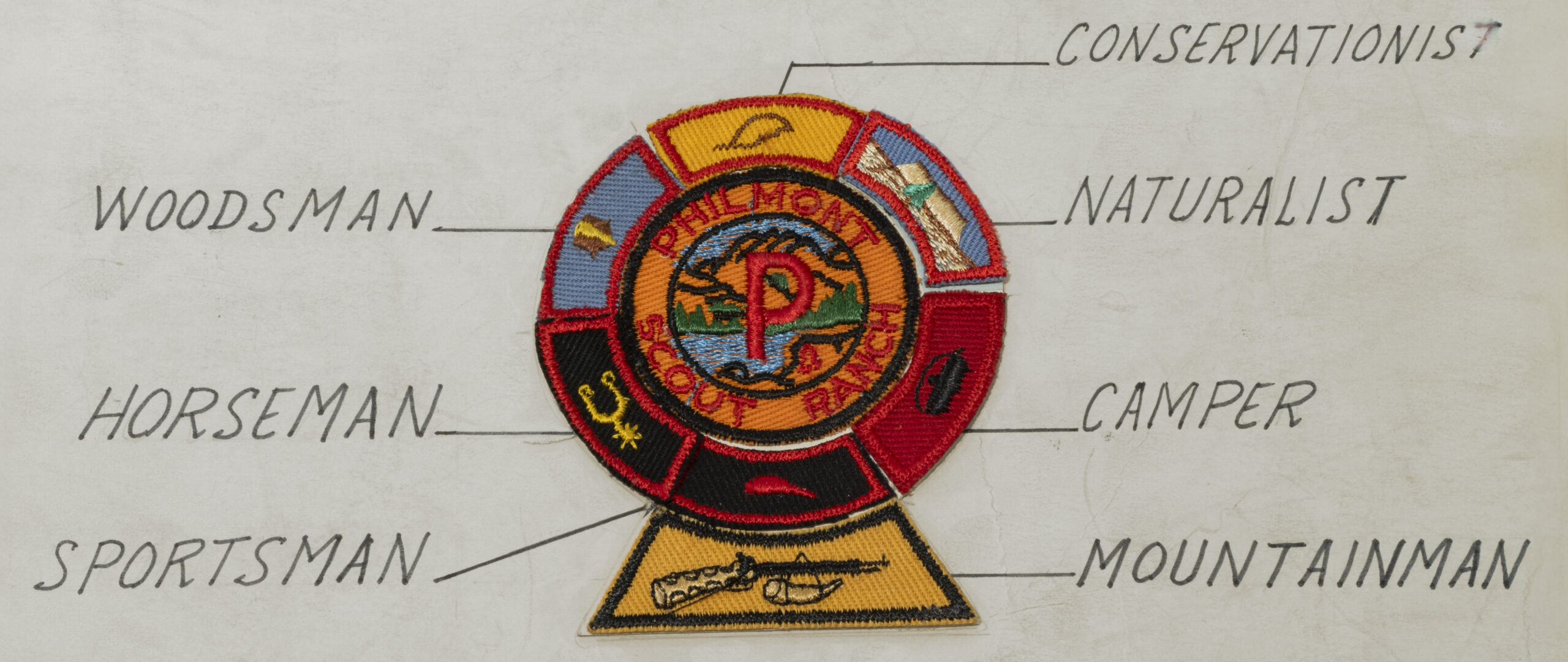

During the 1950s, the Philmont program was focused on exploring the ranch as a member of a crew, a members of a Wagon Train or Cavalcade, a participant in a Kit Carson Trek or Ranch Plan Pioneering Trek, or as a member of a Junior Leaders’ Training Troop. The recognition program associated with these programs was the “Dollar” or “P” patch and its segments. Segments were an outgrowth of the Philmont program and not an end in themselves.

- Philmont Badge (center patch) was given to all Philmont participants.

- The Sportsman (red cap) segment recognized field sports (rifle, shotgun, and fishing).

- The Camper (black pot) was earned for effective backcountry housekeeping.

- The Horseman (yellow spur) was related to learning cowboy history and skills.

- The Conservation (brown beaver lodge) was earned by examining ways to save and protect our natural resources – the predecessor of the similar Arrowhead conservation requirement.

- The Woodsman (brown and yellow cabin) recognized exploring the wilderness heritage of Philmont and was the core of the trek experience.

- The Naturalist (green tree) was related to everything associated with the environment.

- The Mountainman (yellow rifle) was an award given to outstanding campers who had been to Philmont either for three years or completed three schedules.

- Staff Patch (green segment) was presented to staff similarly to the modern-day Staff Arrowhead, which has been since the later 1950s. The staff of Junior Leaders’ Training also used this segment.

Only those who participated in the Wagon Train (23 days) and Junior Leader Training (36 days) had the opportunity to earn all of the segments.

There are minor differences between Dollar patches issued in the 1940s and those issued in the 1950s. The above descriptions are based on the Program Handbook from the 1950s.