Map Orientation

Before hitting the trail, it’s essential to orient your map so that it matches the landscape around you. This means aligning the map with true north using a compass—and adjusting for declination, the difference between magnetic north and true north.

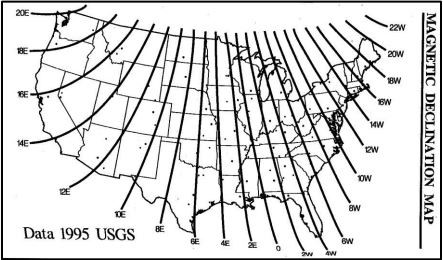

Declination varies by location, so it’s important to know the correct adjustment for your area. A map of declination values for the lower 48 states can help you make this correction. Once your map is properly oriented, you’ll navigate more accurately and confidently throughout your trek.

The declination at Philmont is right around 10° east which means we set our compass at 350.

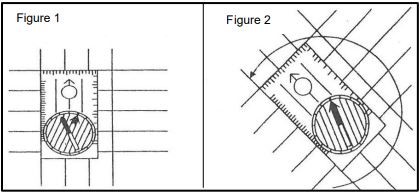

Once the dial is set to 350, align a straight edge of the compass with a grid line on the map so that the compass, not the compass needle, is aligned with north on the map’s compass rose (Figure 1). Then rotate the map (with the compass lying on it) so that the compass needle is pointing toward the N on your compass dial (Figure 2; known as “red in the shed”). Now the map is oriented, and you can accurately decide which trail to take to your destination.

Finding Your Way: UTM Coordinates & Triangulation

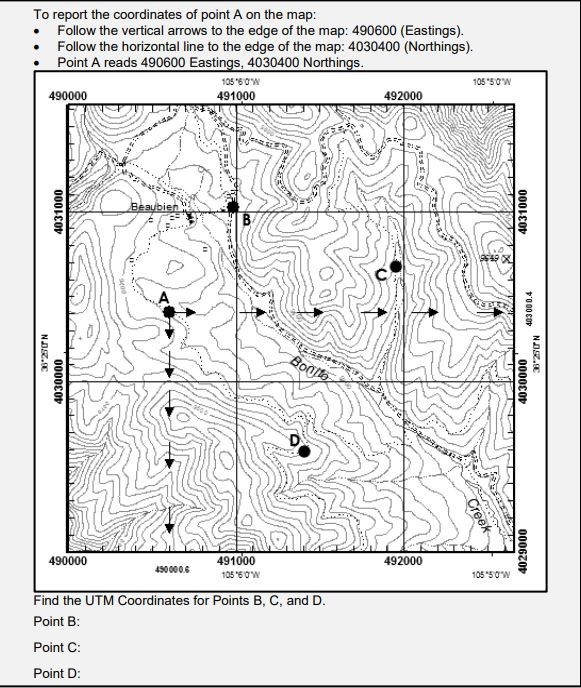

Understanding UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator) coordinates is a powerful way to pinpoint your location or a destination on the trail. UTMs use a metric grid system based on eastings (X-axis) and northings (Y-axis). Always read eastings first, then northings—just like reading across and then up on a graph. At Philmont, many trail signs include UTM coordinates, making it easy to locate yourself on the map and determine your next direction. Just remember to orient your map before using UTMs for accurate results.

Triangulation is another valuable tool for navigation. By using a compass and identifying three visible landmarks, you can draw intersecting lines from each one to estimate your exact position on the map. The more bearings you take, the more precise your location will be. These skills, when practiced, give your crew a clear advantage in confident, safe route finding on your trek.

Starting the Hike

The navigator should set a hiking pace that feels comfortable for every crew member. Clear communication between the front and back of the crew helps maintain this steady pace and prevents anyone from falling behind. Crew members should keep about 8-10 feet of space between each other—but the crew should always stay together as a unit. Before setting off, the navigator should ask, “Is anybody not ready?” This phrasing ensures that any concerns aren’t overlooked—unlike asking, “Is everybody ready?” where a single “no” can easily get lost among many “yes” responses.

Hiking Etiquette

Pace: Your crew should choose a pace that keeps the crew together and allows the crew to hike for extended amounts of time without needing to stop and take a break. If one crew member is significantly slower than the rest of the crew, have them hike near the front of the crew so that they can easily communicate with the navigator/pace setter.

Spacing: It is common for crew members to hike too close together at Philmont and as a result, crew members are not able to see the views and wildlife all around them. It is recommended that crew members are spaced out about 8-10 ft. to allow them to look around and enjoy the views as well as stop in time if the person in front of them were to suddenly stop on the trail. The reason why you do not

want your crew to be too spaced out is that part of the crew may go the wrong way at a trail junction, causing a search and rescue operation because the group was not hiking together as a solidary crew.

Breaks: Crews should take breaks when needed and anyone in the crew should feel comfortable calling for a break. There are two kinds of breaks: a five-minute or less break and a 20-minute or more break. The reason for the two different breaks is the lactic acid buildup that will occur in your muscles after resting for more than five minutes. Lactic acid will leave your muscles feeling sluggish and you will exert much more energy if you hike during lactic acid buildup. After 20 minutes, the lactic acid will dissipate, and your muscles will be able to move unrestricted. Additionally, make sure to never step on the critical edge of the trail, especially when taking breaks. The critical edge is the outside (or downhill) edge of the trail and stepping on it will weaken it and lead to the erosion of the trail.

Passing a Crew: If you encounter another crew heading in the same direction you are hiking, take a five-minute break. If you approach them again, take another five-minute break. If you approach them a third time, ask if you may pass. If you do pass the other crew, do not stop for at least 45 minutes to prevent the two crews from leapfrogging one another.

Another Crew Passes You: As stated earlier, a crew hiking behind you will probably ask if they can pass you. If they do, let them hike in front since you may not have seen them the other two times they approached you. Once passed, taking a five-minute break is a good idea just to give the two crews spacing.

Right of Way: When two crews meet on a hill and are hiking opposite directions, the crew hiking uphill has the right of way and the crew hiking downhill should step off the trail allowing the other crew to pass. The reason for this is that it is harder to get your momentum going uphill than downhill.

Pack Animals: Cavalcade crews or crews with a burro always have the right of way. Listen to the directions of the Horseman or Wrangler for which side of the trail to move to.

Stream Crossings: Cross streams and bridges one person at a time. Unbuckle your hip belt and sternum strap so that if you fall in, you can quickly escape your pack and avoid drowning. The navigator should continue about 30 ft. up the trail and wait for the rest of the crew. When the last person crosses the stream, they should call out “All across” then the navigator will ask the question: “Is anybody not ready?” before hiking on.

Trekking Poles: If you decide to use trekking poles on your trek, make sure to use rubber tips to save our trails from erosion. Trekking poles can reduce the impact on your knees by up to 25% while backpacking but we have found that trails erode much quicker when the sharp tip of the poles are exposed.

Leave No Trace

There are seven principles of Leave No Trace outdoor ethics. Here are the principles and some tips to ensure they are met while on your trek:

- Plan Ahead and Prepare– Knowing the rules and regulations outlined in this guide is a good start to being prepared for your trek. Each night as you are waiting for the water to boil for dinner, it is a good idea to start looking over the map for the next day’s hike. Look for which trails to take, elevation gain, water availability, which camps you will pass through, etc. to get a clear picture of what the day should look like. Proper preparation will allow your crew to get to camp quickly while optimizing your time and program opportunities along the way.

- Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces– Philmont practices concentrated impact camping and has roughly 360 miles of maintained trails, 36 staffed camps, and 86 trail (unstaffed) camps. Hiking and camping on our established trails and campsites (except where they do not exist in the Valle Vidal of the Carson National Forest) allows us to preserve the 99% of land we do not impact. Please follow switchbacks and avoid creating social trails through meadows or riparian areas.

- Dispose of Waste Properly– Every staff camp other than Black Mountain and Crooked Creek accepts consolidated trash. They also collect plastic meal bags, shiny food wrappers (Terracycle), and paperboard. For additional resources on navigation, refer to Scouting America’s Fieldbook and Orienteering Merit Badge Book. Liquid food waste should be poured down the sump and solid food waste should be packed out as trash. Human waste is concentrated into pit-style latrines.

- Leave What You Find– From elk sheds to wildflowers to artifacts; a typical crew will find a variety of items left by the people and animals that have made their home at Philmont over the years. You must only photograph these items and leave them for other crews to enjoy. Anything made by humans that is over 50 years old is considered an artifact and should be left undisturbed. Report anything noteworthy to the next staffed camp you hike through and give them the UTM coordinates so that we may look at it for further investigation.

- Minimize Campfire Impact– As mentioned in Part 1 of this guide, campfires should be kept small. Sticks used as fuel should be no wider than your wrist and no longer than your forearm. Always keep a full pot of water near the fire ring when a campfire is burning. Stir up the coals with a stick and pour water over the coals to ensure the fire is “out cold” before going to bed. When campfires are allowed at Philmont, it is important to dispose of the ashes properly. In the morning as you are ready to leave your campsite, pack the ashes into an empty meal bag and hike them 30 minutes outside of camp then spread the ashes 100 ft. off the trail. This keeps our campsites clean and ready to use for the next crew.

- Respect Wildlife– Philmont’s fauna is varied and includes black bears, mule deer, mountain lions, rattlesnakes, hawks, elk, falcons, cutthroat trout, chipmunks, hummingbirds, raccoons, bighorn sheep, and porcupines, just to name a few. We need to respect these animals by never approaching, throwing rocks, or feeding them. Simply give them distance and let them go about their way. Always hang your smellables up in the bear bags and never leave smellables unattended. Remember, it is common for the quietest crews to see the most wildlife.

- Be Considerate of Other Visitors– With 4,500 people in Philmont’s backcountry at any one time, it is very important to remain respectful towards those around you. This includes not yelling or singing loud songs along the trail or in camp, not writing graffiti, not talking on the cell phone on the summit of mountains, etc. Additionally, highlighter-colored shirts are frowned upon in the backcountry setting, as the bright colors are an eyesore and distraction from the beautiful scenery you will encounter.